Question: An understanding of the nature of Enron’

An understanding of the nature of Enron’s questionable transactions is fundamental to understanding why Enron failed. What follows is an abbreviated overview of the essence of the major important transactions with the SPEs, including Chewco, LJM1, LJM2, and the Raptors. A much more detailed but still abbreviated summary of these transactions is included in the Enron’s Questionable Transactions Detailed Case in the digital archive for this book at www.cengage.com.

Enron had been using specially created companies called SPEs for joint ventures, partnerships, and the syndication of assets for some time. But a series of happenstance events led to the realization by Enron personnel that SPEs could be used unethically and illegally to do the following:

• Overstate revenue and profits

• Raise cash and hide the related debt or obligations to repay

• Offset losses in Enron’s stock investments in other companies

• Circumvent accounting rules for valuation of Enron’s Treasury shares

• Improperly enrich several participating executives

• Manipulate Enron’s stock price, thus misleading investors and enrich- ing Enron executives who held stock options

In November 1997, Enron created an SPE called Chewco to raise funds or attract an investor to take over the interest of Enron’s joint venture investment partner, CalPERS,1 in an SPE called Joint Energy Development Investment Partner- ship (JEDI). Using Chewco, Enron had bought out CalPERS interest in JEDI with Enron-guaranteed bridge financing and tried to find another investor.

Enron’s objective was to find another investor, called a counterparty, which would do the following:

• Be independent of Enron

• Invest at least 3% of the assets at risk

• Serve as the controlling shareholder in making decisions for Chewco

Enron wanted a 3%, independent, con- trolling investor because U.S. accounting rules would allow Chewco to be considered an independent company, and any transac- tions between Enron and Chewco would be considered at arm’s length. This would allow “profit†made on asset sales from Enron to Chewco to be included in Enron’s profit even though Enron would own up to 97% of Chewco. as Chewco’s 3%, independent, controlling investor, and the chicanery began.

Enron was able to “sell†(transfer really) assets to Chewco at a manipulatively high profit. This allowed Enron to show profits on these asset sales and draw cash into Enron accounts without showing in Enron’s financial statements that the cash stemmed from Chewco borrowings and would have to be repaid. Enron’s obligations were understated—they were “hidden†and not disclosed to investors.

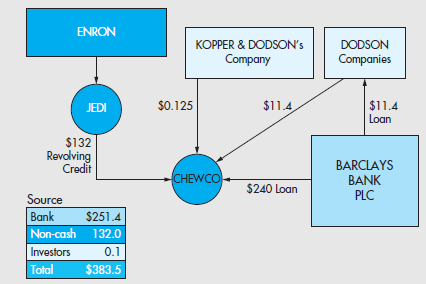

Duplicity is also evident in the way that Chewco’s funding was arranged. CalPERS’s interest in JEDI was valued at $383 million; of that amount, Kopper and/or outside investors needed to be seen to provide 3%, or $11.5 million. The $383 million was arranged as follows2:

These financing arrangements are diagrammed in Figure C2.1.

Essentially, Enron as majority owner put no cash into the SPE. A bank provided virtually all of the cash, and in reality the so-called 3%, independent, controlling investor had very little invested—not even close to the required 3% threshold.

Nonetheless, Chewco was considered to qualify for treatment as an arm’s-length entity for accounting purposes by Enron and its auditors, Arthur Andersen. Enron’s b o a r d—a n d p r es um a b l y A r t h ur Andersen—was kept in the dark.

A number of other issues in regard to Chewco transactions were noted in the Powers Report, including the following:

• Excessive management fees were paid to Kopper for little work.3

• Excessive valuations were used on winding up, thus transferring $10.5 mil- lion to Kopper.

• Kopper sought and received $2.6 mil- lion as indemnification from tax liabil- ity on the $10.5 million.

• Unsecured, nonrecourse loans totaling

$15 million were made to Kopper and not recovered.

• Enron advance-booked revenues from Chewco.

This pattern of financing—no or low Enron cash invested, banks providing most of the funding, and Enron employees masquerading as 3%, independent, con- trolling investors—continued in other SPEs. Some of these SPEs, such as the LJM partner- ships, were used to create buyers for Enron assets over which Enron could keep control but convert fixed assets into cash for growth at inflated prices, thus overstating cash and profits. Other SPEs, such as LJM1 and LJM2, provided illusionary hedge arrangements to protect Enron against losses in its merchant4 investment portfolio, thereby falsely protecting Enron’s reported profits.

In March 1998, Enron invested in Rhythms NetCommunications, Inc. (Rhythms), a business Internet service provider. Between March 1998 and May 1999, Enron’s investment of $10 million in Rhythms stock soared to approximately $300 million. Enron recorded the increase in value as profit by increasing the value of its investment on its books. But Jeffrey K. Skilling, Enron’s CEO, realized that the mark-to- market accounting procedure used would require continuous updating, and the change could have a significant negative effect on Enron’s profits due to the volatility of Rhythms stock price. He also correctly fore- saw that Rhythms stock price could plum- met when the Internet bubble burst due to overcapacity.

LJM1 (LJM Cayman LP) was created to hedge against future volatility and losses on Enron’s investment in Rhythms. If Rhythms stock price fell, Enron would have to record a loss in its investment. However, LJM1 was expected to pay Enron to offset the loss, so no net reduction would appear in overall Enron profit. As with Chewco, the company was funded with cash from other investors and banks based partly on promises of large guaranteed returns and yields. Enron invested its own shares but no cash.

In fact, LJM1 did have to pay cash to Enron as the price of Rhythms stock fell. This created a loss for LJM1 and reduced its equity. Moreover, at the same time as LJM1’s cash was being paid to Enron, the market value of Enron’s shares was also declining, thus reducing LJM1’s equity even further. Ultimately, LJM1’s effective equity eroded, as did the equity of the SPE (Swap Sub) Enron created as a 3% investment conduit. Swap Sub’s equity actually became negative. These erosions of cash and equity exposed the fact that the economic underpin-

ning of the hedge of Rhythms stock was based on Enron’s shares—in effect, Enron’s profit was being hedged by Enron’s own shares. Ultimately, hedging yourself against loss pro- vides no economic security against loss at all. Enron’s shareholders had been misled by $95 million profit in 1999 and $8 mil- lion in 2000. These were the restatements announced in November 2001, just before Enron’s bankruptcy on December 2, 2001.

Unfortunately for Enron, there were other flaws in the creation of LJM1 that ultimately rendered the arrangement useless, but by that time investors had been misled for many years. For example, there was no 3%, independent, controlling investor— Andrew Fastow sought special approval from Enron’s chairman to suspend the conflict of interest provisions of Enron’s Code of Conduct to become the sole managing/ general partner of LJM1 and Swap Sub; and Swap Sub’s equity became negative and could not qualify for the 3% test unless Enron advanced more shares, which it did. Ultimately, as Enron’s stock price fell, Fastow decided the whole arrangement was not sustainable, and it was wound up on March 22, 2000. Once again, the windup arrangements were not properly valued; $70 million more than required was transferred from Enron, and LJM1 was also allowed to retain Enron shares worth $251 million.

Enron’s shareholders were also misled by Enron’s recording of profit on the Treasury shares used to capitalize the LJM1 arrangement. Enron provided the initial capital for LJM1 arrangements in the form of Enron’s own Treasury stock, for which it received a promissory note. Enron recorded this transfer of shares at the existing market value, which was higher than the original value in its Treasury, and therefore recorded a profit on the transaction. Since no cash had changed hands, the price of transfer was not validated, and accounting rules should not have allowed the recording of any profit.

Initially, the LJM1 arrangements were thought to be so successful at generating profits on Treasury shares, hedging against investment losses, and generating cash, that LJM2 Co-Investment LP (LJM2) was created in October 1999 to provide hedges for further Enron merchant investments in Enron’s investment portfolio. LJM2 in turn created four SPEs, called “Raptors,†to carry out this strategy using similar meth- ods of capitalization based on its own Trea- sury stock or options thereon.

For a while, the Raptors looked like they would work. In October 2000, Fastow reported to LJM2 investors that the Rap- tors had brought returns of 193%, 278%, 2,500%, and 125%, which was far in excess of the 30% annualized return described to the finance committee in May 2000. Of course, as we know now, Enron retained the economic risks.

Although nontransparent arrangements were used again, the flaws found in the LJM1 arrangements ultimately became apparent in the LJM2 arrangements, including the following:

• Enron was hedging itself, so no external economic hedges were created.

• Enron’s falling stock price ultimately eroded the underlying equity and cred- itworthiness involved, and Enron had to advance more Treasury shares or options to buy them at preferential rates5 or use them in “costless collarâ€6 arrangements, all of which were further dilutive to Enron earnings per share.

• Profits were improperly recorded on Treasury shares used or sheltered by nonexistent hedges.

• Enron officers and their helpers benefited.

In August 2001, matters became critical. Declining Enron share values and the resulting reduction in Raptor creditworthiness called for the delivery of so many Enron shares that the resulting dilution of Enron’s earnings per share was realized to be too great to be sustainable. In September 2001, accountants at Arthur Andersen and Enron realized that the profits generated by recording Enron shares used for financing at market values was incorrect because no cash was received, and share- holders’ equity was overstated by at least $1 billion.

The overall effect of the Raptors was to misleadingly inflate Enron’s earnings during the middle period of 2000 to the end of the third quarter of 2001 (September 30) by $1,077 million, not including a September Raptor winding-up charge of $710 million.

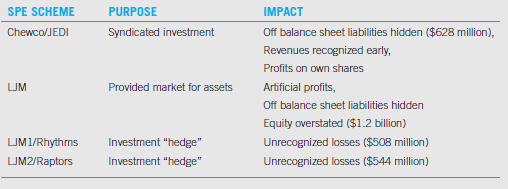

On December 2, 2001, Enron became the largest bankruptcy in the world, leaving investors ruined, stunned, and outraged— and quite skeptical of the credibility of the corporate governance and accountability process. By that time, the Enron SPEs and related financial dealings had misled inves- tors greatly. Almost 50% of the reported profits driving Enron stock up so dramati- cally were false. Table C2.1 summarizes the impacts of Enron’s questionable transac- tions through key Enron SPEs.

Questions

1. Enron’s directors realized that Enron’s conflict of interests policy would be violated by Fastow’s proposed SPE management and operating arrangements, and they instructed the CFO, Andrew Fastow, as an alternative oversight mea- sure, endure that he kept the company out of trouble. What was wrong with their alternatives?

2. Ken Lay was the chair of the board and the CEO for much of the time. How did this probably contribute to the lack of proper governance?

3. What aspects of the Enron governance system failed to work properly, and why?

4. Why didn’t more whistleblowers come forward, and why did some not make a significant difference? How could whistleblowers have been encouraged?

5. What should the internal auditors have done that might have assisted the directors?

6. What conflict-of-interest situations can you identify in the following?

• SPE activities

• Executive activities

7. Why do you think that Arthur Andersen, Enron’s auditors, did not identify the misuse of SPEs earlier and make the board of directors aware of the dilemma?

8. How would you characterize Enron’s corporate culture? How did it contribute to the disaster?

> Should CEOs who made large bonuses by having their firms invest in mortgage-backed securities in the early years have to repay those bonuses in the later years when the firm records losses on those same securities?

> The government bailout of the financial community included taking an equity interest in publicly traded companies such as American International Group (AIG). Is it right for the government to become an investor in publicly traded companies?

> How much should the exiting CEOs of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have received when they were replaced in September 2008?

> Identify and explain five examples where executives or directors faced moral hazards and did not deal with them ethically.

> How could ethical considerations improve unbridled self-interest in ethical decision making?

> Wal-Mart has a brand image that triggers strong reactions in North America, particularly from people whose businesses have been damaged by the company’s over- powering competition with low prices and vast selection and by those who value the small-busine

> How could increased regulation improve the exercise of unbridled self-interest in decision making?

> What were the three most important ethical failures that contributed to the subprime lending fiasco?

> Does the Dodd-Frank Act go far enough, or are some important issues not addressed?

> Should members and executives in investment firms be forced to be members of a profession with entrance exams and with adherence to a professional code such as is the case for professional accountants or lawyers?

> Given that the marketplace for securities is global, and that the risks involved can affect people worldwide, should there be a global regulatory regime to protect investors? If so, should it be based on the regulations of one country? Should enforcement

> The global economic crisis was caused by the meltdown in the U.S. housing market. Should the U.S. government bear some of the responsibility of bailing out the economies of all countries that were harmed by this crisis?

> Are the criticisms that mark-to-market (M2M) accounting rules contributed to the economic crisis valid?

> How much and in which ways did unbridled self-interest contribute to the subprime lending crisis?

> What would you list as the five most important ethical guidelines for dealing with North American employees?

> Do professional accountants have the expertise to audit corporate social performance reports?

> Bernie Madoff perpetrated the world’s largest Ponzi scheme,1 in which investors were initially estimated to have lost up to $65 billion. Essentially, investors were promised—and some received—returns

> Why should a corporation make use of a comprehensive framework for considering, managing and reporting corporate social performance? How should they do so?

> Descriptive commentary about corporate social performance is sometimes included in annual reports. Is this indicative of good performance, or is it just window dressing? How can the credibility of such commentary be enhanced?

> How could a corporation utilize stakeholder analysis to formulate strategies?

> Corporate reporting to stakeholders other than shareholders has exploded. Why is this? Can stakeholders really make good use of all the information now available?

> How will the U.S. external auditor’s mindset change in order to discharge the duties contemplated by SAS 99 on finding fraud?

> If a corporation’s governance process does not involve ethics risk management, what unfortunate consequences might befall a corporation?

> Why should ethical decision making be incorporated into crisis management?

> If a company is to be sentenced for paying bribes 10 years ago, should the company be banned from all government contracts for 10 years, just made to pay a fine, or both? Consider the impacts on all stakeholder groups, including current and past sharehol

> What would you advise that corporations do to recognize the new worldwide reach of antibribery enforcement related to the FCPA and the U.K. Bribery Act?

> How would you advise your company’s personnel to act with regard to expectations of guanxi in China?

> This case presents, with additional information, the WorldCom saga included in this chapter. Questions specific to WorldCom activities are located at the end of the case. WorldCom Lights the Fire WorldCom, Inc., the second-largest U.S. telecommunications

> The #MeToo Movement has finally succeeded in getting women’s allegations of sexual abuse to be taken seriously by management and boards of directors. Why did it take so long for this tipping point to be reached?

> What should a North American company do in a foreign country where women are regarded as secondary to men and are not allowed to negotiate contracts or undertake senior corporate positions?

> Should a North American corporation operating abroad respect each foreign culture encountered, or insist that all employees and agents follow only one corporate culture?

> Is trust really important—can’t employees work effectively for someone they are afraid of or at least where there is some “creative tension”?

> In what ways do ethics risk and opportunity management, as described in this chapter, go beyond the scope of traditional risk management?

> Why is maintaining the confidentiality of client or employer matters essential to the effectiveness of the audit or accountant relationship?

> Which would you chose as the key idea for ethical behavior in the accounting profession: “Protect the public interest” or “Protect the credibility of the profession”? Why?

> When should an accountant place his or her duty to the public ahead of his or her duty to a client or employer?

> Why are most of the ethical decisions accountants face complex rather than straightforward?

> What is meant by the term "fiduciary relationship"?

> Once the largest professional services firm in the world and arguably the most respected, Arthur Andersen LLP (AA) has disappeared. The Big 5 accounting firms are now the Big 4. Why did this happen? How did it happen? What are the lessons to be learned?

> Answer the seven questions in the opening section of this chapter.

> Why do codes of conduct or existing jurisprudence not provide sufficient guidance for accountants in ethical matters?

> Many professional accountants know of questionable transactions but fail to speak out against them. Can this lack of moral courage be corrected? How?

> Transfer pricing can be used to shift profits to jurisdictions with low or no tax to reduce the taxes payable for multinational companies. If such profit shifting is legal, is it ethical? Was Apple well-advised to shift $30 billion in profits to its Iris

> An engineer employed by a large multidisciplinary accounting firm has spotted a condition in a client’s plant that is seriously jeopardizing the safety of the client’s workers. The engineer believes that the professional engineering code requires that t

> Are the governing partners of accounting firms subject to a “due diligence” requirement similar to that for corporation executives in building an ethical culture? Can a firm and/or its governors be sanctioned for the misdeeds of its members?

> What should an auditor do if he or she believes that the ethical culture of a client is unsatisfactory?

> How can a professional accountant develop moral courage?

> Is having an ethical culture important to having an effective system of internal control? Why or why not?

> Why should codes focus on principles rather than specific detailed rules?

> Was the "expectations gap" that triggered the Treadway and Macdonald commissions, the fault of the users of financial statements, the management who prepared them, the auditors, or the standard setters who decided what the disclosure standards should be?

> Are one or more of the fundamental principles found in codes of conduct more important than the rest? Why?

> What is the most important contribution of a professional code of conduct or corporate code of conduct?

> Why does the IFAC Code consider the appearance of a conflict of interests to be as important as a real but non-apparent influence that might sway the independence of mind of a professional accountant?

> If an auditor’s fee is paid from the client company, isn’t there a conflict of interests that may lead to a lack of objectivity? Why doesn’t it?

> Can a professional accountant serve two clients whose interest’s conflict? Explain.

> If you were a professional accountant, and you discovered your superior was inflating his or her expense reports, what would you do?

> If you were a management accountant, would you buy a product from a supplier for personal use at 25% off list?

> How can a professional accountant develop professional skepticism?

> If you were an auditor, would you buy a new car at a dealership you audited for 17% off list price?

> The Prairieland Bank was a medium- sized mid-western financial institution. The management had a good reputation for backing successful deals, but the CEO (and significant shareholder) had recently moved to San Francisco to be “close to the big-bank cent

> If the provision of management advisory services can create conflicts of interest, why are audit firms still offering them?

> An auditor naturally wishes his or her activity to be as profitable as possible, but when, if ever, should the drive for profit be tempered?

> Which type of conflict of interest should be of greater concern to a professional accountant: actual or apparent?

> Independence, as defined on p. 432, seems very straightforward. Why did the IFAC-IESBA 2018 International Code of Conduct for Professional Accountants allocate roughly 50% of its space to cover the International Independence Standards that make up Parts

> Why do more professional accountants not report ethical wrongdoing? Consider their awareness and understanding of ethical issues as well as their motivation and courage for doing so.

> Where on the Kohlberg framework would you place your own usual motivation for making decisions?

> Why did the SEC ban certain non-audit services from being offered to SEC-registrant audit clients even though it has been possible to effectively manage such conflict of interest situations?

> What is the difference between exercising “due care” and “exercising professional skepticism”?

> How do the NOCLAR Standards change the traditional practice of maintaining confidentiality of audit or client information? Why?

> What is the difference between an honest financial statement and one with integrity?

> Sam, I’m really in trouble. I’ve always wanted to be an accountant. But here I am just about to apply to the accounting firms for a job after graduation from the university, and I’m not sure I want to be an accountant after all.” “Why, Norm? In all those

> What is the role of an ethical culture and who is responsible for it?

> How can a company control and manage conflicts of interest?

> Can an apparent conflict of interest where there are adequate safeguards to prevent harm be as important to an executive or a company as one where safeguards are not adequate?

> When should an employee satisfy his or her self-interest rather than the interest of his or her employer?

> What should an employee consider when considering whether to give or receive a gift?

> Explain why corporations are legally responsible to shareholders but are strategically responsible to other stakeholders as well.

> What is the role of a board of directors from an ethical governance standpoint?

> Do professional accountants have the expertise to audit corporate social performance reports?

> Should professional accountants push for the development of a comprehensive framework for the reporting of corporate social performance? Why?

> Descriptive commentary about corporate social performance is sometimes included in annual reports. Is this indicative of good performance, or is it just window dressing? How can the credibility of such commentary be enhanced?

> On April 13, 2006, Bausch & Lomb (B&L) CEO Ron Zarrella indicated that B&L would not be recalling their soft contact lens cleaner Renu with MoistureLoc. Drugstores in the United States were, however, removing the product from their shelves due to a conce

> In Canada, selling body parts, such as organs, sperm and eggs, is illegal. Selling blood is not. Canadian Blood Services, which manages the blood supply for Canadians, neither pays for nor sells blood. It is freely available to whoever needs it. A simila

> If Lynn Stout is correct, that the drive for shareholder value is a myth, why do so many companies continue to use it as a goal?

> Why is it suspected that corporate psychopaths gravitate to certain industries, and what should corporations within those industries do about it?

> If you were asked to evaluate the quality of an organization’s ethical leadership, what would the five most important aspects be that you would wish to evaluate, and how would you do so?

> Why should an effective whistle-blower mechanism be considered a “failsafe mechanism” in SOX Section 404 compliance programs?

> Is the SOX-driven effort being made to check on the effectiveness of internal control systems worth the cost? Why and why not?

> Other than a code of conduct, what aspects of a corporate culture are most important and why?

> How can a corporation integrate ethical behavior into their reward and remuneration schemes?

> How could you monitor compliance with a code of conduct in a corporation?

> Why should codes focus on principles rather than specific detailed rules?

> Are one or more of the fundamental principles found in codes of conduct more important than the rest? Why?

> Mega Brands has been selling Magnetix toys for many years. It also sells Mega Bloks, construction toys based on Spider-Man, Pirates of the Caribbean, as well as other products in over 100 countries. In 2006, Mega Brands had over $547 million in revenue,

> What is the most important contribution of a corporate code of conduct?

> Must a company be incorporated as a benefit corporation in order to legally consider actions other than those in pursuit of profit?

> From a virtue ethics perspective, why would it be logical to put in place a manufacturing process beyond legal requirements?

> How can a decision to down-size be made as ethically as possible by treating everyone equally?

> How would you convince a CEO not to treat the environment as a cost-free commons?

> Under what circumstances would it be best to use each of the following frameworks: the philosophical set of consequentialism, deontology, and virtue ethics; the modified 5-question; the modified moral standards; and the modified Pastin approach?