Question: Jack O’Brien is a PhD student

Jack O’Brien is a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh. Jack is working on a PhD thesis on the role of negative emotions, and more specifically the emotion anger, in service consumption settings. Jack’s dissertation aims to supply service providers with knowledge to prevent anger and to adequately deal with customers experiencing anger, both on a strategic and operational level. On a strategic level, his dissertation will support service firms with respect to decision-making and services marketing management. On an operational level, it will first and foremost offer service providers information for avoiding customer anger and dealing with angry customers.

To emphasize the practical relevance of his work, Jack and his supervisor have agreed to undertake an exploratory, qualitative study into the prevalence of customer anger. Jack has carried out this study last month. Recently, he has been writing up a first draft of this research project.

The Prevalence of Anger in Services – FIRST DRAFT – Jack O’Brien

Customers may experience a wide range of emotions in response to a service encounter. Previous research has mentioned joy, satisfaction, dissatisfaction, disappointment, anger, contempt, fear, shame, and regret, to name only a few (Nyer, 1999; Westbrook, 1987; Zeelenberg and Pieters, 1999; 2004). One of these emotions, anger, has profound effects on customers’ behavioral responses to failed service encounters, such as switching and negative word-of-mouth communication (Bougie, Zeelenberg, and Pieters, 2003; Grégoire and Fisher, 2008; Grégoire, Laufer, and Tripp, 2010, Nyer, 1999; Taylor, 1994). In turn, switching and negative word-of-mouth communication (directly or indirectly) affect the profitability of service firms. Hence, the basic emotion research finding that anger is also a common emotion - experienced by most of us anywhere from several times a day to several times a week (Averill, 1982) - suggests that anger may have a strong impact on the profitability and performance of service firms.

However, the afore-mentioned findings on the prevalence of anger do not necessarily apply to service consumption settings. For instance, Averill shows that the most common target of anger is a loved one or a friend: “anger at others, such as strangers and those whom we dislike is not usual†(1982, p. 169). Averill provides a number of possible reasons for this finding, such as increased chances that a provocation will occur, a stronger motivation to get loved ones to change their ways, the more cumulative and distressing nature of provocations committed by loved ones, the tendency to give strangers the benefit of the doubt, and the tendency to avoid those who we dislike. It is therefore unclear whether anger is frequently experienced in service settings.

This study aims to fill this gap in our knowledge by investigating whether anger is commonly experienced in response to failed service encounters. The results of this study provide increased insights into the prevalence of anger in services and thus into the effects of customer anger on the profitability and performance of service firms.

Method:

Procedure. The critical incident technique (CIT) was used as a method. Flanagan (1954) defines the CIT as ‘a set of procedures for collecting direct observations of human behavior in such a way as to facilitate their potential usefulness in solving practical problems and developing broad psychological principles’. It involves several steps, including the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. Critical incidents were collected by research assistants, who were carefully trained to gather the data. They were encouraged to accumulate data from 100 participants using convenience sampling. In order to obtain a sample representative of customers of service organizations, they were instructed to collect data from a wide variety of people. Participants were asked to record their critical incidents on a standardized form.

Participants. One hundred and eighteen persons were approached to participate in this study. Fourteen persons indicated that they were either unwilling or unable to participate and four questionnaires were eliminated because of incompleteness. Eventually, 60 men and 40 women, ranging in age from 16 to 95, with a median age of 27, stayed in the sample: 3% of them had less than a high school education, whereas 25% had at least a bachelor’s degree.

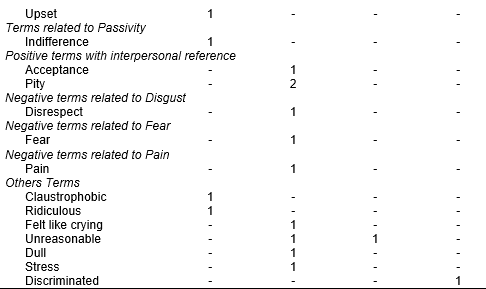

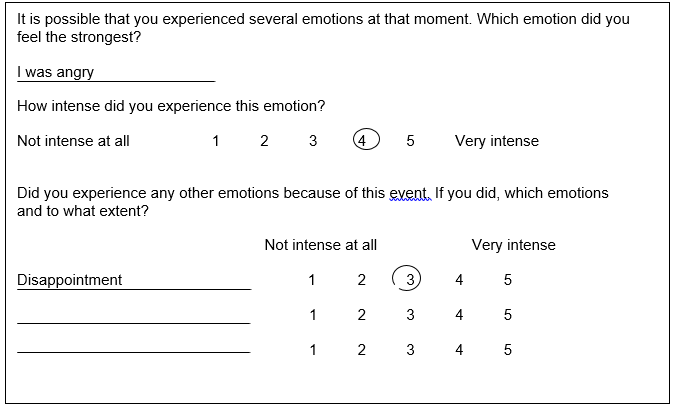

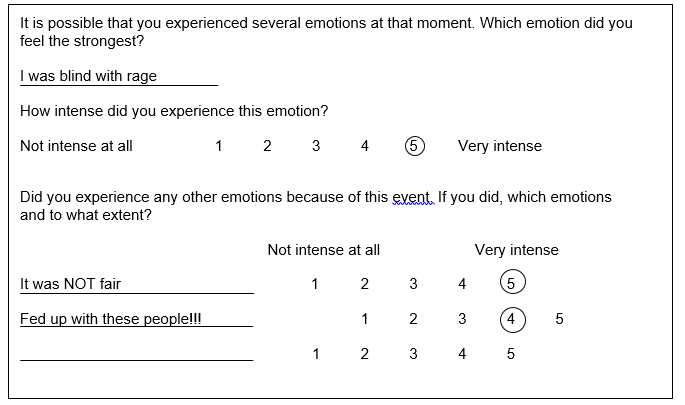

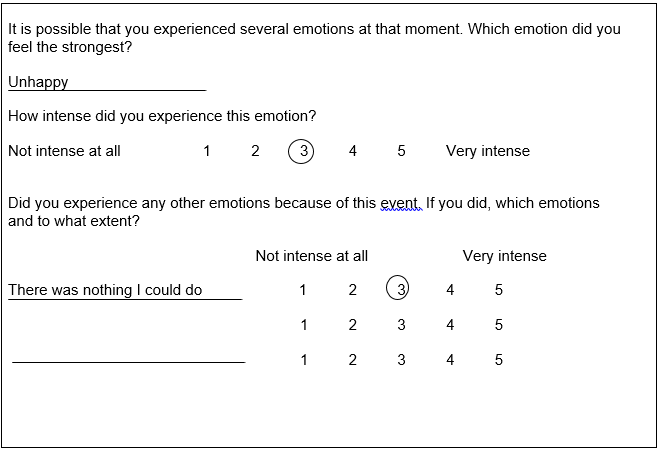

Questionnaire. The first question asked participants to indicate which of 29 different services they had purchased during the previous six-month period. This question was asked to reduce participants’ uncertainty regarding what was meant by services and to check whether participants had purchased services during the last six months (cf., Keaveney, 1995). Then, participants were asked to recall the last negative experience with a service provider and to bring back as much of the actual experience as they possibly could. They were asked to describe this experience in an open-ended format. Next, participants were asked to indicate if they experienced any emotions as a result of the negative experience with the service provider. Then they were asked which emotions they experienced as a result of the service failure by means of open-ended questions. The open-ended questions were “It is possible that you experienced several emotions at that moment. Which emotion did you feel the strongest?â€

Subsequently, a closed-ended question was asked about the intensity of the reported emotion. The question “How intense did you experience this emotion?†was answered on a five-point scale with end-points labeled not intense at all (1) and very intense (5). Finally, participants were asked whether they had experienced any other emotions because of this event, and if they had, which emotions (open-ended question) and to what extent (closed-ended question).

Data categorization. A classification based on the results of a taxonomic study of the vocabulary of emotions by Storm and Storm (1987) was used to categorize the results of this study. This particular taxonomy was chosen because Storm and Storm used a rigorous system to classify a large number of emotion terms into an adequate and comprehensive number of categories and subcategories: first, they used a sorting task and hierarchical clustering to identify a preliminary set of categories; then they expanded the words to be classified into these categories by asking various groups of participants to supply words related to feelings; and finally, four expert judges sorted the larger collection of words into categories. The result was a taxonomy that contains 525 different emotion terms distributed among seven categories and twenty subcategories. The categories include three negative emotion categories, two positive emotion categories, and two categories referring to cognitive states or physical conditions. Subcategories include shame, sadness, pain, anxiety, fear, anger, hostility, disgust, love, liking, contentment, happiness, pride, sleepy, apathetic, contemplative, arousal, interest, surprise, and understanding.

Results:

Negative service experiences. The participants of this study reported a wide variety of negative service experiences. Reported service failures fell in the categories of personal transportation (by airplane, taxi, or train), banking and insurance, entertainment, hospitality, and restaurants, (virtual) stores, hospitals, physicians, and dentists, repair and utility services,(local) government and the police, education, telecommunication companies, health clubs, contracting firms, hairdressers, real-estate agents, driving schools and travel agencies. On average, the negative events that participants reported had happened 9.5 weeks before.

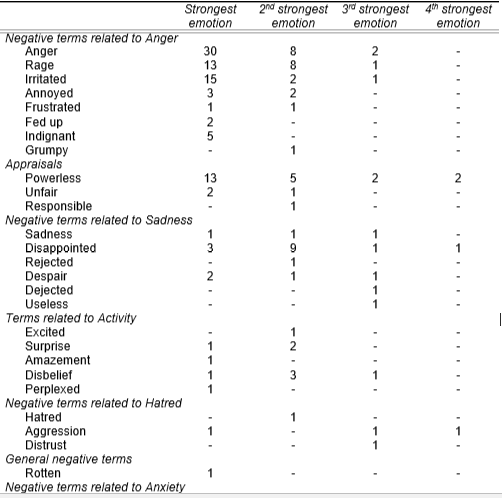

Experienced emotions. The aim of this study was to investigate whether anger is commonly experienced in response to failed service encounters. The participants of this study experienced a broad range of negative emotions in response to a failed service encounter. The emotion terms customers provided were classified into seven categories: anger, sadness, hatred, anxiety, disgust, fear, and pain. Other terms that were mentioned were classified into four additional categories provided by the classification of Storm and Storm (1987): general negative terms, positive terms with interpersonal reference, terms related to passivity, and terms related to activity. Finally, two additional categories, appraisals, and a category labeled ‘other terms’ were included to classify terms that did not tie in with the classification scheme of Storm and Storm.

On average, the participants provided 1.78 emotion terms: 5 participants experienced four emotions; 10 participants experienced three emotions; 43 participants experienced two emotions; and 42 participants experienced one emotion. Table 1 provides an overview of the results of this study.

Negative terms related to anger were mentioned most often. Anger terms were mentioned 95 times, corresponding to 53.37% of all items. Eighty-two percent of the participants mentioned a negative term related to anger (either as the most intensely experienced emotion or as the second-, third-, or fourth-strongest emotion). Sixty-nine percent of the participants mentioned a negative term related to anger as the most intense emotion. The specified anger terms include ‘Angry’, ‘Rage’, ‘Irritated’, ‘Annoyed’, ‘Frustrated’, ‘Fed up’, ‘Indignant’, and ‘Grumpy’.

The second largest category is appraisals; cognitions associated with the perceived antecedents of emotions. Participants mentioned three different appraisals, ‘powerless’, ‘unfair’, and ‘responsible’. Note that prior research associates the appraisal ‘unfair’ with anger, whereas ‘powerless’ is associated with both anger and sadness (Ruth et al., 2002; Shaver et al., 1987).

The third largest cluster is ‘Negative terms related to Sadness’. Sadness terms were mentioned 24 times by 21 participants. This category includes the emotion terms ‘Sad’, ‘Rejected’, ‘Disappointed’, ‘Despair’, ‘Dejected’, and ‘Useless’.

Other categories are considerably smaller than the afore-mentioned categories. Besides the afore-mentioned appraisals, eight further ‘emotion’ terms that the participants of this study provided did not fit the taxonomy of Storm and Storm (1987). As customers employed a rather broad definition of emotion, the emotion terms they provided included mood states, action tendencies, and opinions about the event and/or the service provider. These terms were categorized as ‘Other terms’.

Multiple emotions. Fifty-eight participants mentioned more than one term: however, only 17 of them experienced multiple emotions. Anger and sadness were experienced most often in combination (14 times), followed by anger and fear (2 times) and fear and sadness (1 time).

Intensity of emotions. On a five-point scale, ranging from not intense at all (1) to very intense (5), the mean rating of the strongest emotion was 3.97. Moreover, the large majority of the responses (84%) fell above the midpoint of the scale. This suggests that the participants of this study did not report incidents that they considered trivial or inconsequential.

Table 1: Customers’ Emotions in Response to Failed Service Encounters

Table 1:

Note. The numbers in the second, third, fourth, and fifth column refer to how many times a specific emotion term was mentioned as respectively the strongest, second-strongest, third-strongest, or fourth-strongest emotion. A dash indicates that this emotion was not mentioned (as for instance the strongest emotion).

Discussion:

The results of this study demonstrate that consumers experience a broad range of negative emotions in response to a failed service encounter. Anger was by far the most frequently experienced emotion; 82% of the participants experienced anger in response to the most recently experienced failed service encounter. This suggests that anger is a common emotion in response to failed service encounters. Because the results of this study provide additional support for the contention that customer anger has a powerful impact on the profitability and performance of service firms, this study calls for more research on the nature of customer anger.

References

Averill, James R. (1982) Anger and Aggression: An Essay on Emotion. New York: Springer Verlag.

Bougie, R., R. Pieters, and M. Zeelenberg (2003), Angry Customers Don't Come Back, They Get Back: The Experience and Behavioral Implications of Anger and Dissatisfaction in Services. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31, 377-393.

Flanagan, J. C. (1954), The Critical Incident Technique. Psychological Bulletin, 51, 327-358.

Keaveney, Susan M. (1995), “Customer Switching Behavior in Service Industries: An Exploratory Study,†Journal of Marketing, 59 (April), 71-82.

Grégoire, Y. and R. Fisher (2008) Customer Betrayal and Retaliation: When Your Best Customers Become Your Worst Enemies, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 2008, 36, 247-261

Grégoire Y., D. Laufer, and T. Tripp (2010), A Comprehensive Model of Customer Direct and Indirect Revenge: Understanding the Effects of Perceived Greed and Customer Power, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 738-758.

Nyer, P. U. (1999). The Effects of Satisfaction and Consumption Emotion on Actual Purchasing Behavior. Journal of Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction and Complaining Behavior, 11, 62-68.

Ruth, Julie A., Frédéric F. Brunel, and Cele C. Otnes (2002), “Linking Thoughts to Feelings: Investigating Cognitive Appraisals and Consumption Emotions in a Mixed Emotions Context,†Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30, (1) 44-58.

Shaver, P., J. Schwartz, D. Kirson, and C. O’Connor (1987). Emotion Knowledge: Further Exploration of the Prototype Approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 1061-1086.

Storm, Christine and Tom Storm (1987), “A Taxonomic Study of the Vocabulary of Emotions,†Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, (4) 805-816.

Taylor, Shirley (1994), “Waiting for Service: The Relationship Between Delays and Evaluations of Service,†Journal of Marketing, 58 (April), 56-69.

Westbrook, R. A. (1987). Product/Consumption-Based Affective Responses and Postpurchase Processes. Journal of Marketing Research, 24, 258-270.

Zeelenberg, M. and R. Pieters (1999). Comparing Service Delivery to What Might Have Been: Behavioral Responses to Regret and Disappointment. Journal of Service Research, 2,

86 97.

Zeelenberg, M. and R. Pieters (2004). Beyond Valence in Customer Dissatisfaction: Behavioral Responses to Regret and Disappointment in Failed Services. Journal of Business Research, 57, 445-455

QUESTIONS:

1. Why are the data that Jack has gathered qualitative in nature?

2. Jack has gathered qualitative data via a questionnaire. Describe three other techniques and/or sources to gather qualitative data.

3. Sampling for qualitative research is as important as sampling for quantitative research. Purposive sampling is one technique that is often employed in qualitative investigation (see Chapter 13). Describe purposive sampling.

4. How do you feel about the sampling technique that Jack has used (convenience sampling)? Would you have preferred purposive sampling? Why (not)?

5. Describe the three steps in qualitative data analysis (data reduction, data display, and the drawing of conclusions) on the basis of Jack’s study.

6. Jack has not paid any attention to the reliability and validity of his results in the first draft of his study.

a. Are reliability and validity altogether important in qualitative research?

b. Discuss reliability and validity in qualitative research.

c. Describe how Jack could have paid attention to the reliability and validity of his findings.

7. Please categorize the following three responses into Jack’s classification system.

Transcribed Image Text:

Strongest emotion 2nd strongest 3rd strongest 4th strongest emotion emotion emotion Negative terms related to Anger Anger Rage Irritated Annoyed Frustrated 30 13 15 8. 8 2 1 1 1 Fed up Indignant Grumpy Appraisals Powerless Unfair Responsible Negative terms related to Sadness Sadness Disappointed Rejected Despair Dejected Useless Terms related to Activity Excited Surprise Amazement 1 13 2 2 1 1 1 3 2 1 1 Disbelief Perplexed Negative terms related to Hatred Hatred Aggression Distrust General negative terms Rotten Negative terms related to Anxiety 1 1 1 1 1 191 유은3125- Upset Terms related to Passivity 1 Indifference 1 Positive terms with interpersonal reference Acceptance Pity Negative terms related to Disgust Disrespect Negative terms related to Fear Fear 1 2 1 1 Negative terms related to Pain Pain 1 Others Terms Claustrophobic Ridiculous 1 1 Felt like crying Unreasonable Dull Stress Discriminated 1 It is possible that you experienced several emotions at that moment. Which emotion did you feel the strongest? I was angry How intense did you experience this emotion? Not intense at all 1 2 3 4 5 Very intense Did you experience any other emotions because of this event, If you did, which emotions and to what extent? Not intense at all Very intense Disappointment 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 It is possible that you experienced several emotions at that moment. Which emotion did you feel the strongest? I was blind with rage How intense did you experience this emotion? Not intense at all 1 2 3 4 Very intense Did you experience any other emotions because of this event, If you did, which emotions and to what extent? Not intense at all Very intense It was NOT fair 1 2 3 4 (5 Fed up with these people!!! 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 5 It is possible that you experienced several emotions at that moment. Which emotion did you feel the strongest? Unhappy How intense did you experience this emotion? Not intense at all 1 2 3 4 5 Very intense Did you experience any other emotions because of this event, If you did, which emotions and to what extent? Not intense at all Very intense There was nothing I could do 1 2 3) 4 5 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 5 5,

> The data below show the number of enterprises in the United Kingdom in 2010, arranged according to employment: Number of employees Number of firms 1 ……………………………………………………………. 1 740 685 5 ……………………………………………………………. 388 990 10 ……………………………………………………………. 215

> Sketch the probability distribution for the number of accidents on a stretch of road in one day.

> A train departs every half hour. You arrive at the station at a completely random moment. Sketch the probability distribution of your waiting time. What is your expected waiting time?

> Construct a chain index for 2001–10 using the following data, setting 2004 = 100. 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 87 95 100 105 98 93 100 104 110 100 106 112

> Demonstrate that the weighted average calculation given in equation (1.9) is equivalent to finding the total expenditure on education divided by the total number of pupils.

> The following data show the education and employment status of women aged 20–29: a. Draw a bar chart of the numbers in work in each education category (the first line of the table). Can this be easily compared with the similar diagram

> How does moderate participation differ from complete participation?

> Discuss how ethnography and participant observation are related.

> Define reliability and validity in the context of qualitative research.

> How does narrative analysis differ from content analysis?

> What is grounded theory?

> How can you assess the reliability and validity of qualitative research?

> A production manager wants to assess the reactions of the blue‐collar workers in his department (including foremen) to the introduction of computer‐integrated manufacturing (CIM) systems. He is particularly interested to know how they perceive the effect

> David Shen Liang is a business student engaged in a management project for Ocg Business Services (OBS), a supplier of office equipment to a large group of (international) customers. OBS operates in the Businessto‐business market. David

> Critique Report 3 in the Appendix. Discuss it in terms of good and bad research, suggesting how the study could have been improved, what aspects of it are good, and how scientific it is.

> The following data are available: Note: Maximum exam mark = 100, Maximum paper mark = 100, Sex: M = male, F = female, Year in college: 1 = Freshman; 2 = Sophomore; 3 = Junior; 4 = Senior. 1. Data handling a. Enter the data in SPSS. Save the file to yo

> Dear Respondent, I am final year student studying Business Information Technology (BIT). For my research project I am conducting a survey related to online buying. It would be great if you could answer some questions about this topic. There are no right

> T-Mobile is a mobile network operator headquartered in Bonn, Germany. The company has enlisted your help as a consultant to develop and test a model on the determinants of subscriber churn in the German mobile telephone market. Develop a sampling plan an

> The Executive board of a relatively small university located in Europe wants to determine the attitude of their students toward various aspects of the University. The university, founded in 1928, is a fully accredited government financed university with

> A consultant had administered a questionnaire to some 285 employees using a simple random sampling procedure. As she looked at the responses, she suspected that two questions might not have been clear to the respondents. She would like to know if her sus

> A magazine article suggested that “Consumers 35 to 44 will soon be the nation’s biggest spenders, so advertisers must learn how to appeal to this “over-the-thrill crowd”. If this suggestion appeals to an apparel manufacturer what should be the sampling d

> The medical inspector desires to estimate the overall average monthly occupancy rates of the cancer wards in 80 different hospitals which are evenly located in the Northwestern, Southeastern, Central, and Southern suburbs of New York city.

> Develop an ordinal scale for consumer preferences for different brands of cars.

> Suggest two variables that would be natural candidates for nominal scales, and set up mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive categories for each.

> The SERVQUAL-scale described in the appendix is formative in nature.” Comment on this statement. Explain why it does not make sense to assess the inter-item consistency of this scale.

> Develop and name the type of measuring instrument you would use to tap the following: a. Which brands of toothpaste are consumed by how many individuals? b. Among the three types of exams – multiple choice, essay type, and a mix of both – which is the o

> Mention one variable for each of the four scales in the context of a market survey, and explain how or why it would fit into the scale.

> Dawson Chambers is a young, dynamic and fast growing research agency that is specialized in Mystery Shopping, Market Research, and Customer Service Training. It is located in Geneva, Switzerland from where it provides national and international organizat

> Measure any three variables on an interval or a ratio scale.

> Design an interview schedule to assess the “intellectual capital” as perceived by employees in an organization – the dimensions and elements for which you developed earlier.

> a. Read the paper by Cacioppo and Petty (1982) and describe how the authors generated the pool of 45 scale items that appeared relevant to need for cognition. b. Why do we need 34 items to measure “need for cognition”? Why do three or four items not suf

> Identify the object and the attribute. Give your informed opinion about who would be an adequate judge. a. Price consciousness of car buyers. b. Self‐esteem of dyslexic children. c. Organizational commitment of school teachers. d. Marketing orientati

> Find the paper “Consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation,” written by Marsha Richins and Scott Dawson. a. Provide an overview of the dimensions and elements of Richins and Dawson’s materialism sca

> Compare your service quality measure to the measure of Zeithaml, Berry, and Parasuraman (1996) presented in the Journal of Retailing. a. How does your measure differ from this measure in terms of dimensions and elements? b. Would you prefer using your

> Try to come up with two unidimensional and two multidimensional abstract concepts. Explain why these concepts have either one or more than one dimension.

> What are projective techniques and how can they be profitably used?

> Explain the possible ways in which you can control “nuisance” variables.

> What is bias and how can it be reduced while interviewing?

> Kyoto Midtown is a composite urban district of modern buildings surrounding a historic Japanese garden. It features sophisticated bars, restaurants, shops, art galleries, a hotel and leafy public spaces. Kyoto Midtown aims to offer a unique shopping expe

> As a manager, you have invited a research team to come in, study, and offer suggestions on how to improve the performance of your staff. What steps would you take to allay their apprehensions even before the research team sets foot in your department?

> Describe different data sources, explaining their usefulness and disadvantages.

> Explain the concept of “trade-off” between internal and external validity.

> What is internal validity and what are the threats to internal validity?

> Define the terms control and manipulation. Describe a possible Lab experiment where you would need to control a variable. Further, include a possible variable over which you would have no control, that could affect your experiment.

> In what ways do Lab experiments differ from Field experiments?

> What are the differences between causal and correlational studies?

> The Solomon Four Group Design is the answer to all our research questions pertaining to cause and effect relationships because it guards against all the threats to internal validity. Comment.

> If a control group is a part of an experimental design, one need not worry about controlling for other exogeneous variables. Discuss this statement.

> Explain why mortality remains a problem even when a Solomon four-group design is used.

> History is a key problem in a time series design. “Other problems are main and interactive testing effects, mortality, and maturation.” Explain.

> Explain the difference between main and interactive testing effects. Why is this difference important?

> Explain how the selection of participants may affect both the internal and external validity of your experiments.

> How has the advancement of technology helped data gathering?

> How are multiple methods of data collection and from multiple sources related to reliability and validity of the measures?

> Explain the principles of wording, stating how these are important in questionnaire design, citing examples not in the book.

> How has the advancement of technology helped data gathering via questionnaires?

> One way to deal with discrepancies found in the data obtained from multiple sources is to average the figures and take the mean as the value on the variable. What is your reaction to this?

> Every data-collection method has its own built-in biases. Therefore, resorting to multi-methods of data collection is only going to compound the biases. Critique this statement.

> Provide relevant measurable attributes for the following objects. a. a restaurant; b. an investment banker; c. a consumer; d. a bicycle; e. a pair of sunglasses; f. a strategic business unit.

> When Song Mei Hui moved from being Vice President for Human Resources at Pierce & Pierce in Shanghai to her international assignment in New York, she was struck by the difference in perception of Pierce & Pierce as an employer in China and the Un

> Under which circumstances would you prefer observation as a method to collect data over other methods of data collection such as interviews and questionnaires?

> How is the interval scale more sophisticated than the nominal and ordinal scales?

> Describe the four types of scales

> Field notes are often regarded as being simultaneously data and data analysis. Why?

> What is rapport and how is rapport established in participant observation?

> Although participant observation combines the processes of participation and observation it should be distinguished from both pure observation and pure participation. Explain.

> Operationalize the following: a. customer loyalty b. price consciousness c. career success.

> Why is it important to establish the “goodness” of measures and how is this done?

> What aspects of a class research project would be stressed by you in the written report and in the oral presentation?

> Why is it necessary to specify the limitations of the study in the research report?

> In 1965, a young man named Fred DeLuca wanted to become a medical doctor. Looking for a way to pay for his education, a family friend – Peter Buck – advised him to open a submarine sandwich shop. With a loan of $1,000,

> How have technological advancements helped in writing and presenting research reports?

> What are the similarities and differences of basic and applied research reports?

> Discuss the purpose and contents of the Executive Summary.

> What is bootstrapping and why do you think that this method is becoming more and more popular as a method of testing for moderation and mediation?

> A tax consultant wonders whether he should be more selective about the class of clients he serves so as to maximize his income. He usually deals with four categories of clients: the very rich, rich, upper middle class, and middle class. He has informatio

> What kinds of biases do you think could be minimized or avoided during the data analysis stage of research?

> There are three measures of central tendencies: the mean, the median, and the mode. Measures of dispersion include the range, the standard deviation, and the variance (where the measure of central tendency is the mean), and the interquartile range (where

> What is reverse scoring and when is reverse scoring necessary?

> How would you deal with missing data?

> Data editing deals with detecting and correcting illogical, inconsistent, or illegal data in the information returned by the participants of the study. Explain the difference between illogical, inconsistent, and illegal data.

> In the first months of 2010, U.S. Banks have launched a campaign that aims to win back trust of their consumers and repair their battered images. For banks, it is very important to rectify the violation of trust caused by the financial crisis if the fina

> Double sampling is probably the least used of all sampling designs in organizational research. Do you agree? Provide reasons for your answer.

> Over-generalizations give rise to a lot of confusion and other problems for researchers who try to replicate the findings. Explain what is meant by this.

> Because there seems to be a tradeoff between accuracy and confidence for any given sample size, accuracy should be always considered more important than precision. Explain with reasons, why you would or would not agree with this statement.

> Nonprobability sampling designs ought to be preferred to probability-sampling designs in some cases. Explain with an example.

> Use of a sample of 5,000 is not necessarily better than having a sample of 500. How would you react to this statement?

> The use of a convenience sample in organizational research is correct because all members share the same organizational stimuli and go through almost the same kinds of experiences in their organizational life. Comment.

> a. Explain what precision and confidence are and how they influence sample size. b. Discuss what is meant by the statement: “There is a trade‐off between precision and confidence under certain conditions.

> a. Explain why cluster sampling is a probability sampling design. b. What are the advantages and disadvantages of cluster sampling? c. Describe a situation where you would consider the use of cluster sampling.

> Why do you think the sampling design should feature in a research proposal?

> Identify the relevant population for the following research foci, and suggest the appropriate sampling design to investigate the issues, explaining why they are appropriate. Wherever necessary, identify the sampling frame as well. a. A company wants to

> The Standard Asian Merchant Bank is a Malaysian merchant bank headquartered in Kuala Lumpur. The bank provides financial services in asset management, corporate finance, and securities broking. Clients of The Standard Asian Merchant Bank are among others

> Construct a semantic differential scale to assess the properties of a particular brand of tea or coffee.

> Explain why it does not make sense to assess the internal consistency of a formative scale.

> Describe the difference between formative and reflective scales.

> Briefly describe the difference between attitude rating scales and ranking scales and indicate when the two are used.

> Discuss the ethics of concealed observation.

> Why is the ratio scale the most powerful of the four scales.

> Tables 15.A to 15.D below summarize the results of data analyses of research conducted in a sales organization that operates in 50 different cities of the country and employs a total sales force of about 500. The number of salespe